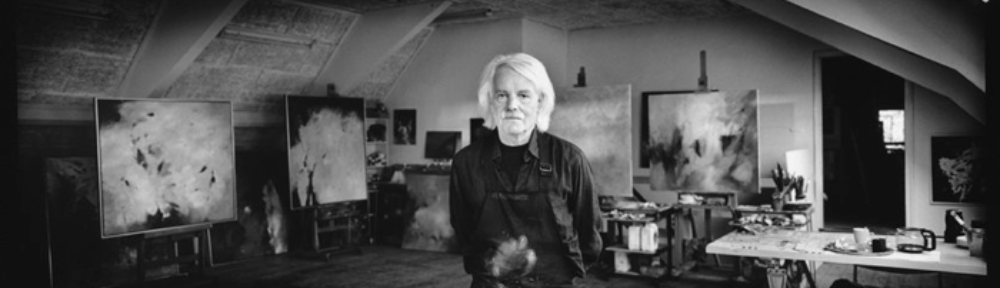

Jan Aanstoot

The book Jan Aanstoot • 25 is a tribute to 25 years of artistry. One page after the other shows us the work of the painter Jan Aanstoot and the developments within that work. All those pictures also intrigue the reader. Who exactly is Jan Aanstoot, what is his background, what was at the basis of his artistic calling, what are his ideas on painting, what exactly does he have in mind with all that work?

What strikes one most when looking for answers to those questions is how inconsequential and even misleading the usual lists with personal details can be. Jan’s list is as follows:

born

in Wierden (1948)

education

grammar school and teacher training college in Almelo, and the art academy in Arnhem from 1969 onwards

work

employed as an art teacher after his years at the academy, – until 2007 – the last 31 years of that period at the erstwhile Thij College in Oldenzaal

place of residence

Wierden, from 1948 up to now.

Those facts are correct, but at the same time they say nothing about the most essential thing, something that is rather incongruous in such a list of details: being superior to such trivialities, Jan expressly made up his mind to follow his artistic calling and painted an impressive oeuvre. This he mainly did at home, in Wierden, but also in his small studio in Paris. In galleries in France he opened exhibitions of his paintings in fluent French, he showed his work at the Biennale Internationale del’Arte Contemporanea in Florence, in Dubai he succeeded in getting gallery owners enthusiastic about exhibitions of his canvases, and in the

summer of 2010 there was a solo exhibition in the ‘Fortezza del

Girifalco’ in Cortona, Italy. What’s more, to him Wierden was and is not just the place in this country to live, and also to work in the seclusion of his house and nowadays of his studio, but at the same time he likes to

dedicate himself on a regular basis to initiatives that have a stimulating effect on the cultural life of his place of residence. A list of personal details is thoroughly inadequate.

Let’s look back: Jan Aanstoot was the second child in a hard-working family of tradespeople, in a traditional Reformed environment. His parents ran a butcher’s shop and when Jan was a child it was self-evident that he and his three sisters would lend a hand whenever necessary. One of those duties was delivering orders in the village, with a bag full of change. But at an early age he was made responsible for window dressing and the advertising material, because even then his artistic talent attracted attention. The cliché of the culturally narrow-minded background of traditional Calvinism, however, by no means applied to the Aanstoot family. Music, for example, was a matter of course: there was a harmonium in the house and later on a piano, and Jan’s musical and visual talents were taken seriously and encouraged. So his parents were certainly not to blame for the fact that Jan suddenly gave up his music lessons. It was the fault of a teacher who found it hard to sympathize with a pupil who had to bike from Wierden to Almelo (6 km,

4 miles) in all weathers to play études with frozen fingers. It is true that music still plays a role in his life, but an enthusiastic teacher might have encouraged him to go to music school, Jan now thinks – without regret, but rather with a sense of curiosity about what a life of music could have been like.

However much Jan’s parents appreciated and stimulated his artistic talents, it did not mean that they felt that being an artist was a realistic professional option. Their basic principle was that first and foremost you had to have security in terms of income and employment. The teacher training college, as the course for teachers in primary education was called in those days, fitted into that picture. It did not take long for Jan to discover that being a primary school teacher was not his cup of tea at all. He did finish the course, however, and made sure that he passed the examinations for his teaching certificate and his lower art-teaching qualification, thus clearing the way for an advanced study of art. The logical next stage in that development was the art academy, to be trained as a teacher of art.

The five years at the Arnhem art academy were dominated by very hard work indeed: a combination of attending lectures and giving lessons in order to do his part for the income of his young family. They were long days, at the academy: driving to Arnhem early in the morning to go through a heavy programme starting at nine, back again at the end of the afternoon in his Citroen 2 CV, then studying hard for college in the evening – all very disciplined. A student life was not to be his part, and a trip to Florence that was part of the course simply was beyond his means. In spite of the hard work, or perhaps for that very reason, they were fantastic years. It was a very thorough course, its curriculum devoted much attention to various aspects of realistic art, such as figure and portrait study and anatomy, and Jan managed to apply the knowledge he acquired there during the long hours of making paintings and watercolours. Practical painting lessons meant that students worked completely independently, not receiving comment on their work until much later. In retrospect, Jan feels that this was a shortcoming. As a matter of fact one of his most important experiences was that, at some stage, someone entered the room where he was working, watched what he was doing over his shoulder, and said casually: ‘I’d do that a bit more loosely’. It has come to serve as a guiding principle for Jan’s work to this day.

Being a student between 1968 and 1973 also meant witnessing or perhaps even taking part in all sorts of radical changes in education. It was the beginning of the great theoretical process. If you took your study of anatomy seriously, you were more or less considered a traitor, because you were supposed to study the views of Marcuse and Adorno and the rest of the Frankfurter Schule. Things even reached the stage where later generations of students flatly refused to attend practical lessons at the academy. But to Jan, practice has always remained the main thing, regardless of the extent to which philosophy and theory could help provide insight. He was very much aware of the false use of these very theories: participating in the theorizing also had the effect of raising your status: you were not just some artist, but you could present yourself with some neo-Marxist, philosophical story that was perfectly in tune with the character of the era.

Obviously it was the art of painting itself that was his main drive, despite everything that theory could offer in the way of insight. Even prior to the academy he greatly admired impressionists like George Breitner and Isaac Israëls, and he had become acquainted with expressionism through the work of the artist Berry Brugman from Almelo. Teaching at the academy was firmly based on realism. Pop art and photo realism were the prevailing styles of those years and their influence was so strong that many students only painted from photographs. Jan never did; he was one of the exceptions who continued to attend anatomy classes, although obviously there, too, realistic reproduction was the basis. In the years after the academy, until the mid-eighties, Jan went looking for a way to break out of this rigid realistic pattern and to find a method of working that would be looser and freer. Painting watercolours played an important part in that development. It is remarkable when one realizes that the focal point of the developments leading towards his later artistry was the school holidays. It was intensive work: on the camping site in France the watercolour paper was mounted in the evening, he did his painting in the morning, the afternoon was spent looking for a spot for the next day, and then the cycle started once again in the evening.

And let’s not forget: after his years at the academy Jan continued to teach in secondary education. For many artists such a position was a means to earn an income, at any rate, to build up a pension, to have health insurance; in other words, to form a solid basis for a family life. Obviously this also applied to Jan, but being a teacher meant a lot more to him than just a source of income. The man who realized within a few months at teacher training college that the last thing he should be was a primary school teacher became an inspiring teacher in secondary education. He felt that in those lessons the point at issue was not the talented pupils, because they were perfectly capable of making new steps under their own steam, with some minor instruction. What mattered more than anything else to him was the awareness that anybody can learn a lot and that, even without being particularly gifted, you can achieve a certain level. He tried to motivate young people into learning things in a good and pleasant atmosphere, appealing to their dignity: ‘the way I treat you, I wish to be treated by you’. And it worked. At his school, the erstwhile Thij College in Oldenzaal, art was a subject that counted, one in which you could sit an exam. Those examination classes were always well to very well attended and a fair share of those pupils later opted for some sort of creative schooling. To Jan’s way of thinking, something else was even more important: the pupils who preferred not to take that exam, but still continued to draw with great pleasure and effort. That’s what mattered to him, and the feeling that he was achieving important aims with his pupils ensured that he managed to cope with the frustration caused by endless meetings and the circus of budgets for a considerable time.

In spite of his success in teaching, he was increasingly faced with a dilemma in the early eighties. The urge to do creative work himself became so strong that the school holidays no longer offered enough time, so that more and more ‘private time’ went into painting. In 1985, the ensuing tension led to drastic changes in his personal situation. The alternatives were obvious: he was to undertake the day-to-day care of his children, being an artist was the main thing from now on and he remained in the employ of the school. It meant a lot of hard work, what with the school and the family by day and an astonishing production of work, particularly on paper, in the evening. It looked as if a blocked pipe had burst open, with all the creativity that issued forth. Being able to get to work seriously at last, that was the underlying feeling of relief. Then there was the additional aspect that his environment accepted this choice. To his children, pupils at the Free School, and his relatives, culture was a matter of course. That made things easier, but it was far from simple. Emotionally charged though it was, that choice offered the opportunity for the artist’s existence that Jan managed to realize.

To the outsider it may seem that the changes in his personal life also led to a break in an artistic sense: away from realism, preferring an ever-further development of abstract-expressionism. Jan has a slightly different view of the subject. He is of the opinion that it was not a break, but rather the acceleration of a process that had already begun. The realism of yet another series of watercolours became too easy, painting seemed to have become a routine activity, and this he found threatening. The choice for the artistic calling involved the necessity to realize an awareness of what exactly he had in mind when it came to art. In addition, this had resulted in a different kind of freedom, a freedom that spread its effects to all fields. Broadening his areas of attention, dissociating himself from familiar frameworks, letting go of matters – it all had an astonishingly stimulating effect. Even now, that urge to continue changing is still present. Of course, his work harmonizes with a certain modernist tradition and it is not radically innovative, but Jan will say that, in a personal sense, that innovation certainly exists.

Broadening your area of special attention, finding a certain modernist tradition: such definitions demand to know what Jan’s work was influenced by. He has never lost his predilection for impressionists like Isaac Israëls, being moved by their looseness and freedom. At a later stage they were joined by artists such as Cézanne and Bonnard and expressionists such as Kandinsky, Nolde and Van Dongen. The post-war abstract-expressionism of painters like Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning and certainly the action painting of Jackson Pollock and the later material painters such as Burri and Tapiès are all part of Jan’s enumeration of great examples. Many aspects of the art he admires converge in Anselm Kiefer’s work: it is partly material art, it is expressionist in its concepts and, moreover, it is very sound in its relation to the historical reality represented. In this country, Emo Verkerk and, with some reservations, Armando and Marlène Dumas are among the favourites. It is a varied and impressive list: Jan has a great capacity for admiration, that much is clear.

In that enumeration of art he admires, a number of lasting standards can be recognized. In the first place there is the appreciation of the way artists use their material, e.g., in the freedom of the material painters, or in the grand brushstrokes in De Kooning’s paintings and the role of coincidence in Jackson Pollock’s drippings. A second standard is the intensity of the imagination, with Rothko’s work as the acme. A third is the relation to historical reality as in Kiefer’s work but also in Armando’s series of paintings entitled Fahnen, for example. Traces of that admiration can certainly be found in his own work, in his search for the freedom of painting loosely for example, but likewise in a number of small paintings that bring all sorts of associations to the mind of the beholder of the fate of prisoners and refugees. This may seem to be remote from the major part of his oeuvre, but from time to time he feels the urge to visualize what affects him from a social point of view.

In the last century, the change from realistic to abstract work was accompanied by a discussion of a great many different aspects. The relation between image and reality, the possibly transcendental character of art, the relation between rationality and intuition, the interpretation of the meaning of the work of art, these are questions an abstract artist cannot easily ignore. Views such as Piet Mondriaan’s, where abstracting was supposed to reveal a deeper, more fundamental reality, have never been the mainspring of Jan’s work, even though he believes that something essential may be revealed inadvertently and spontaneously. Jan feels that the relationship between spirituality and painting can be found in something entirely different: spirituality is a form of dealing with one’s own freedom, averse to conformism and constantly on the look-out for the correct image. It is a form of being unbound that is reflected in the work of art.

‘Loose, free, unbound’ are key words. Such concepts affect the relationship between rationality and intuition in the way Jan’s paintings are created. The painting process begins with a source of inspiration: anything that enters the mind can be used. Music plays an important part here, although there is no direct link between a certain composition or composer and a specific painting. In Jan’s view, there is a certain relationship between the language of music and his own visual language. Both seem to have come into existence intuitively, but at the same time the basis is complex and it is in that very combination of intuition and complexity that the search for a certain harmony takes place. The harmonious aspect is not necessarily found in something charming and pleasant – dreary looking paintings need a harmony of their own just as much. It is found ‘on the job’, trying to find a balance independent of all kinds of trivialities. You have to sit down from time to time and look at your work, and go on looking until you feel what the painting needs. Then you will find the details that enable harmony.

And then comes the moment when the painting is finished and displayed to people. This also means that the painting is assigned meanings. To many abstract artists, including Jan, it is an invariable that a work of art is not ‘finished’ until it is seen by the viewer. With a fair amount of overstatement, one might say that viewers do this in two ways. The first one is that the painting is ‘read’ as a psychogram of the artist. If the painting evokes emotions, it means that the artist had to find some way of giving free rein to his own emotions and voilà: … here they are, on the canvas! The second way works just the other way round: the painting turns into a place where the viewer’s own ideas and feelings are found. Both approaches are psychological in nature and Jan will not reject them off-hand but, as he sees it, the meaning of his work is different. It is not true that he induces an emotion and then sets out to paint it. First of all, there is a certain image that forces itself upon him and demands to be painted. Where it springs from, which experiences or emotions, is not something that particularly interests him; all that matters is this image, the size and form and colour. Whether or not the image will be visualized at the end of the day is an entirely different matter altogether. While painting, you constantly come across new elements. Some of them are rejected while working, others find an unexpected place, changing what had once served as the point of departure. That search, that is what really matters to Jan: painting as a process that results in an image that makes you realize that this was what you had been looking for all the time. Looking for what is unsought and attempting to visualize it: that is the crux of his entire oeuvre.

Thijs Weststrate